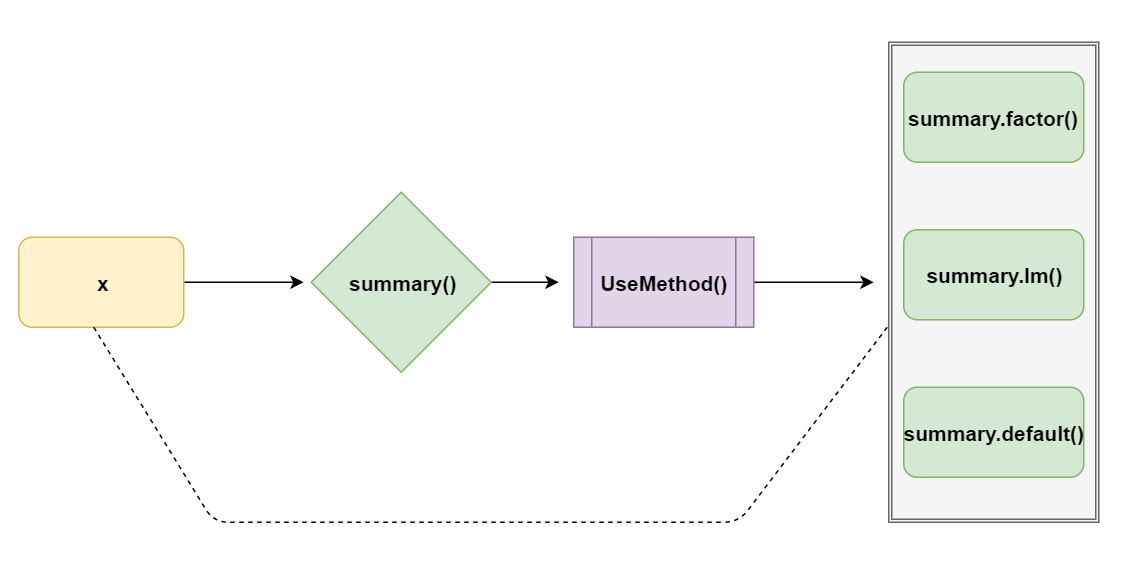

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Subsetting and S3 objects ## Programming for Statistical Science ### Shawn Santo --- ## Supplementary materials Full video lecture available in Zoom Cloud Recordings Companion videos - [Subsetting matrices and data frames](https://warpwire.duke.edu/w/31UEAA/) Additional resources - [Object oriented program introduction](https://adv-r.hadley.nz/oo.html), Advanced R - [Chapter 12](https://adv-r.hadley.nz/base-types.html), Advanced R - [Sections 13.1 - 13.4](https://adv-r.hadley.nz/s3.html), Advanced R - Create your own S3 vector classes with package [vctrs](https://vctrs.r-lib.org/articles/s3-vector.html) --- class: inverse, center, middle # Recall --- ## Subsetting techniques R has three operators (functions) for subsetting: 1. `[` 2. `[[` 3. `$` Which one you use will depend on the object you are working with, its attributes, and what you want as a result. We can subset with - integers - logicals - `NULL`, `NA` - character values --- class: inverse, center, middle # Subsetting matrices, arrays, and data frames --- ## Subsetting matrices and arrays ```r (x <- matrix(1:6, nrow = 2, ncol = 3)) ``` ``` #> [,1] [,2] [,3] #> [1,] 1 3 5 #> [2,] 2 4 6 ``` .pull-left[ ```r x[1, 3] ``` ``` #> [1] 5 ``` ```r x[1:2, 1:2] ``` ``` #> [,1] [,2] #> [1,] 1 3 #> [2,] 2 4 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r x[, 1:2] ``` ``` #> [,1] [,2] #> [1,] 1 3 #> [2,] 2 4 ``` ```r x[-1, -3] ``` ``` #> [1] 2 4 ``` ] --- ## Do I always get a matrix (array) in return? .pull-left[ ```r x[1, ] ``` ``` #> [1] 1 3 5 ``` ```r attributes(x[1, ]) ``` ``` #> NULL ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r x[, 2] ``` ``` #> [1] 3 4 ``` ```r attributes(x[, 2]) ``` ``` #> NULL ``` ] -- For matrices and arrays `[` has an argument `drop = TRUE` that coerces the result to the lowest possible dimension. -- .tiny[ ```r x[1, , drop = FALSE] ``` ``` #> [,1] [,2] [,3] #> [1,] 1 3 5 ``` ```r attributes(x[1, , drop = FALSE]) ``` ``` #> $dim #> [1] 1 3 ``` ] --- ## Preserving vs simplifying subsetting Type | Simplifying | Preserving :----------------|:-------------------------|:----------------------------------------------------- Atomic Vector | `x[[1]]` | `x[1]` List | `x[[1]]` | `x[1]` Matrix / Array | `x[1, ]` <br/> `x[, 1]` | `x[1, , drop=FALSE]` <br/> `x[, 1, drop=FALSE]` Factor | `x[1:4, drop=TRUE]` | `x[1:4]` Data frame | `x[, 1]` <br/> `x[[1]]` | `x[, 1, drop=FALSE]` <br/> `x[1]` By preserving we mean retaining the attributes. It is good practice to use `drop = FALSE` when subsetting a n-dimensional object, where `\(n > 1\)`. <br/> The drop argument for factors controls whether the levels are preserved or not. It defaults to `drop = FALSE`. --- ## Subsetting data frames Recall that data frames are lists with attributes `class`, `names`, `row.names`. Thus, they can be subset using `[`, `[[`, and `$`. They also support matrix-style subsetting (specify rows and columns to subset). ```r df <- data.frame(coin = c("BTC", "ETH", "XRP"), price = c(10417.04, 172.52, .26), vol = c(21.29, 8.07, 1.23) ) ``` -- What will the following return? .pull-left[ ```r df[1] df[c(1, 3)] df[1:2, 3] df[, "price"] ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r df[[1]] df[["vol"]] df[[c(1, 3)]] df[[1, 3]] ``` ] ??? What will the following return? .tiny[ .pull-left[ ```r df[1] ``` ``` #> coin #> 1 BTC #> 2 ETH #> 3 XRP ``` ```r df[c(1, 3)] ``` ``` #> coin vol #> 1 BTC 21.29 #> 2 ETH 8.07 #> 3 XRP 1.23 ``` ```r df[1:2, 3] ``` ``` #> [1] 21.29 8.07 ``` ```r df[, "price"] ``` ``` #> [1] 10417.04 172.52 0.26 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r df[[1]] ``` ``` #> [1] "BTC" "ETH" "XRP" ``` ```r df[["vol"]] ``` ``` #> [1] 21.29 8.07 1.23 ``` ```r df[[c(1, 3)]] ``` ``` #> [1] "XRP" ``` ```r df[[1, 3]] ``` ``` #> [1] 21.29 ``` ] ] --- class: inverse, center, middle # Subsetting extras --- ## Subassignment Indexing can occur on the right-hand-side of an expression for extraction or on the left-hand-side for replacement. ```r x <- c(1, 4, 7) ``` ```r x[2] <- 2 x ``` ``` #> [1] 1 2 7 ``` -- ```r x[x %% 2 != 0] <- x[x %% 2 != 0] + 1 x ``` ``` #> [1] 2 2 8 ``` -- ```r x[c(1, 1, 1, 1)] <- c(0, 7, 2, 3) ``` What is `x` now? -- ```r x ``` ``` #> [1] 3 2 8 ``` ??? Subassignment is done sequentially, so if an index is specified more than once the latest assigned value for an index will result. --- .pull-left[ ```r x <- 1:6 x[c(2, NA)] <- 1 x ``` ``` #> [1] 1 1 3 4 5 6 ``` ```r x <- 1:6 x[c(TRUE, NA)] <- 1 x ``` ``` #> [1] 1 2 1 4 1 6 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r x <- 1:6 x[c(-1, -3)] <- 3 x ``` ``` #> [1] 1 3 3 3 3 3 ``` ```r x <- 1:6 x[] <- 6:1 x ``` ``` #> [1] 6 5 4 3 2 1 ``` ] --- ## Adding list and data frame elements ```r df <- data.frame( x = rnorm(4), y = rt(4, df = 1) ) ``` -- .tiny[ ```r df$z <- rchisq(4, df = 1) df ``` ``` #> x y z #> 1 -3.4809589 -0.1352990 0.417447011 #> 2 0.5808455 0.1701396 0.002165436 #> 3 1.2596732 -0.7547219 1.353941825 #> 4 2.1495364 -0.3276574 1.147967281 ``` ] -- .tiny[ ```r df["a"] <- rexp(4) df ``` ``` #> x y z a #> 1 -3.4809589 -0.1352990 0.417447011 0.7779105 #> 2 0.5808455 0.1701396 0.002165436 0.7652353 #> 3 1.2596732 -0.7547219 1.353941825 1.0843019 #> 4 2.1495364 -0.3276574 1.147967281 0.5968456 ``` ] --- ## Removing list and data frame elements .tiny[ ```r df <- data.frame(coin = c("BTC", "ETH", "XRP"), price = c(10417.04, 172.52, .26), vol = c(21.29, 8.07, 1.23) ) ``` ] .tiny[ ```r df["coin"] <- NULL str(df) ``` ``` #> 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 2 variables: #> $ price: num 10417.04 172.52 0.26 #> $ vol : num 21.29 8.07 1.23 ``` ```r df[[1]] <- NULL str(df) ``` ``` #> 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 1 variable: #> $ vol: num 21.29 8.07 1.23 ``` ```r df$vol <- NULL str(df) ``` ``` #> 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 0 variables ``` ] --- ## Exercises Use the built-in data frame `longley` to answer the following questions. 1. Which year was the percentage of people employed relative to the population highest? Return the result as a data frame. 2. The Korean war took place from 1950 - 1953. Filter the data frame so it only contains data from those years. 3. Which years did the number of people in the armed forces exceed the number of people unemployed? Give the result as an atomic vector. ??? ## Solutions 1. .tiny[ ```r longley[which.max(longley$Employed / longley$Population), "Year", drop=FALSE] ``` ``` #> Year #> 1956 1956 ``` ] 2. .tiny[ ```r longley[longley$Year %in% 1950:1953, ] ``` ``` #> GNP.deflator GNP Unemployed Armed.Forces Population Year Employed #> 1950 89.5 284.599 335.1 165.0 110.929 1950 61.187 #> 1951 96.2 328.975 209.9 309.9 112.075 1951 63.221 #> 1952 98.1 346.999 193.2 359.4 113.270 1952 63.639 #> 1953 99.0 365.385 187.0 354.7 115.094 1953 64.989 ``` ] 3. .tiny[ ```r longley$Year[longley$Armed.Forces > longley$Unemployed] ``` ``` #> [1] 1951 1952 1953 1955 1956 ``` ] --- class: inverse, center, middle # S3 objects --- ## Introduction >S3 is R’s first and simplest OO system. S3 is informal and ad hoc, but there is a certain elegance in its minimalism: you can’t take away any part of it and still have a useful OO system. For these reasons, you should use it, unless you have a compelling reason to do otherwise. S3 is the only OO system used in the base and stats packages, and it’s the most commonly used system in CRAN packages. <br><br> Hadley Wickham <br/> R has many object oriented programming (OOP) systems: S3, S4, R6, RC, etc. This introduction will focus on S3. --- ## Polymorphism How are certain functions able to handle different types or classes of inputs? ```r summary(c(1:10)) ``` ``` #> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. #> 1.00 3.25 5.50 5.50 7.75 10.00 ``` -- ```r summary(c("A", "A", "a", "B", "b", "C", "C", "C")) ``` ``` #> Length Class Mode #> 8 character character ``` -- ```r summary(factor(c("A", "A", "a", "B", "b", "C", "C", "C"))) ``` ``` #> a A b B C #> 1 2 1 1 3 ``` --- ```r summary(data.frame(x = 1:10, y = letters[1:10])) ``` ``` #> x y #> Min. : 1.00 Length:10 #> 1st Qu.: 3.25 Class :character #> Median : 5.50 Mode :character #> Mean : 5.50 #> 3rd Qu.: 7.75 #> Max. :10.00 ``` -- ```r summary(as.Date(0:10, origin = "2000-01-01")) ``` ``` #> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. #> "2000-01-01" "2000-01-03" "2000-01-06" "2000-01-06" "2000-01-08" "2000-01-11" ``` --- ## Terminology - An **S3 object** is a base type object with at least a class attribute. - The implementation of a function for a specific class is known as a **method**. - A **generic function** defines an interface that performs method dispatch.  --- ## Example  ```r x <- factor(c("A", "A", "a", "B", "b", "C", "C", "C")) summary(x) ``` ``` #> a A b B C #> 1 2 1 1 3 ``` --- ## Example .pull-left[ ```r summary.factor(x) ``` ``` #> a A b B C #> 1 2 1 1 3 ``` ```r summary.default(x) ``` ``` #> a A b B C #> 1 2 1 1 3 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r summary.lm(x) ``` ``` #> Error: $ operator is invalid for atomic vectors ``` ```r summary.matrix(x) ``` ``` #> Warning in seq_len(ncols): first element used of 'length.out' argument ``` ``` #> Error in seq_len(ncols): argument must be coercible to non-negative integer ``` ] --- ## Working with the S3 OOP system Approaches for working with the S3 system: 1. build methods off existing generics for a newly defined class; 2. define a new generic, build methods off existing classes; 3. or some combination of 1 and 2. --- ## Approach 1 First, define a class. S3 has no formal definition of a class. The class name can be any string. ```r x <- "hello world" attr(x, which = "class") <- "string" x ``` ``` #> [1] "hello world" #> attr(,"class") #> [1] "string" ``` -- Second, define methods that build off existing generic functions. Functions `summary()` and `print()` are existing generic functions. -- ```r summary.string <- function(x) { length(unlist(strsplit(x, split = ""))) } ``` -- ```r print.string <- function(x) { print(unlist(strsplit(x, split = "")), quote = FALSE) } ``` --- ## Approach 1 in action ```r summary(x) ``` ``` #> [1] 11 ``` -- ```r print(x) ``` ``` #> [1] h e l l o w o r l d ``` -- ```r y <- "hello world" summary(y) ``` ``` #> Length Class Mode #> 1 character character ``` ```r print(y) ``` ``` #> [1] "hello world" ``` --- ## Approach 2 First, define a generic function. ```r trim <- function(x, ...) { UseMethod("trim") } ``` -- Second, define methods based on existing classes. ```r trim.default <- function(x) { x[-c(1, length(x)), drop = TRUE] } ``` -- ```r trim.data.frame <- function(x, col = TRUE) { if (col){ x[-c(1, dim(x)[2])] } else { x[-c(1, dim(x)[1]), ] } } ``` --- ## Approach 2 in action .tiny.pull-left[ ```r trim(1:10) ``` ``` #> [1] 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ``` ```r trim(c("a", "ab", "abc", "abcd")) ``` ``` #> [1] "ab" "abc" ``` ```r trim(c(T, F, F, F, T)) ``` ``` #> [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE ``` ```r trim(factor(c("a", "ab", "abc", "abcd"))) ``` ``` #> [1] ab abc #> Levels: ab abc ``` ] -- .tiny.pull-right[ ```r df <- data.frame(x = 1:5, y = letters[1:5], z = rep(T, 5)) df ``` ``` #> x y z #> 1 1 a TRUE #> 2 2 b TRUE #> 3 3 c TRUE #> 4 4 d TRUE #> 5 5 e TRUE ``` ```r trim(df) ``` ``` #> y #> 1 a #> 2 b #> 3 c #> 4 d #> 5 e ``` ```r trim(df, col = FALSE) ``` ``` #> x y z #> 2 2 b TRUE #> 3 3 c TRUE #> 4 4 d TRUE ``` ] --- ## Helpful tips - When creating new classes follow Hadley's recommendation of constructor, validator, and helper functions. See section [13.3](https://adv-r.hadley.nz/s3.html#s3-classes) in Advanced R. - Only write a method if you own the generic or class. - A method must have the same arguments as its generic, except if the generic has the `...` argument. ``` > print function (x, ...) UseMethod("print") > print.data.frame function (x, ..., digits = NULL, quote = FALSE, right = TRUE, row.names = TRUE, max = NULL) ``` - Package `sloop` has useful functions for finding generics and methods. Specifically, `ftype()`, `s3_methods_generic()`, `s3_methods_class()`. - Use the generic function and let method dispatch do the work, i.e. use `print(x)` and not `print.data.frame(x)` if `x` is a data frame. --- ## Exercises 1. Use function `sloop::ftype()` to see which of the following functions are S3 generics: `mean`, `summary`, `print`, `sum`, `plot`, `View`, `length`, `[`. 2. Choose 2 of the S3 generics you identified above. How many methods exist for each? Use function `sloop::s3_methods_generic()`. 3. How many methods exist for classes `factor` and `data.frame`. Use function `sloop::s3_methods_class()`. 4. Consider a class called accounting. If a numeric vector has this class, function `print()` should print the vector with a $ in front of each number and display values up to two decimals. Create a method for this class. The next slide provides a demonstration. --- ## Demo for exercise four *Hint*: ```r format(round(-3:3, digits = 2), nsmall = 2) ``` ``` #> [1] "-3.00" "-2.00" "-1.00" " 0.00" " 1.00" " 2.00" " 3.00" ``` -- ```r x <- 1:5 class(x) <- "accounting" print(x) ``` ``` #> [1] $1.00 $2.00 $3.00 $4.00 $5.00 ``` ```r y <- c(4.292, 134.1133, 50.111) class(y) <- "accounting" print(y) ``` ``` #> [1] $ 4.29 $134.11 $ 50.11 ``` ??? ## Part 4 ```r print.accounting <- function(x) { print(paste0("$", format(round(x, digits = 2), nsmall = 2)), quote = FALSE) } ``` ```r x <- 1:5 class(x) <- "accounting" print(x) ``` ```r y <- c(4.292, 134.1133, 50.111) class(y) <- "accounting" print(y) ``` --- ## References 1. R Language Definition. (2020). Cran.r-project.org. https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-lang.html 2. Wickham, H. (2020). Advanced R. https://adv-r.hadley.nz/